Phytotechnology – Why would you combine science, engineering and landscape architecture?

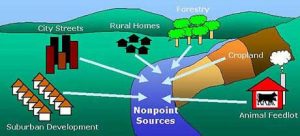

Over the last several decades we have introduced several categories of non-point source pollutants and contaminants into our environment. From Creosote and PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) to Arsenic, Lead and BTEX contaminants like solvents, gasoline, and heavy metals are all twentieth century chemical introductions to our environment.

Over the last several decades we have introduced several categories of non-point source pollutants and contaminants into our environment. From Creosote and PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) to Arsenic, Lead and BTEX contaminants like solvents, gasoline, and heavy metals are all twentieth century chemical introductions to our environment.

Phytotechnology is a rapidly developing field of study that implements living plant solutions to cleanup contaminated sites, a. combination of science, engineering, and landscape architecture. This system considers the use of ecosystems in the development of a solution to an environmental contaminant problem.

Due to the different properties of these substances, there are several ways, or technologies to remediate them depending on if the content is organic, or inorganic. You can:

1. Take up the contaminants and either degrade or harvest them;

2. Keep all the metals down, stabilizing pollutants onsite like lead and keeping them out of harms way

3. Take precautionary strategies implementing Phyto Sensors; i.e. the use of plants to alert a business owner or property owner of leakage or spillage before it gets out of hand.

These environmental pollutants are introduced to our environment in stormwater, air, soil and ground water. Plants work as a reactor – the plant releases sugars, oxygen, water and enzymes while taking other chemicals up from the ground. Our plants behave like living pumps.

Plants are Living Pumps

Many organic compounds, i.e. chemical compounds that contain bonds with oxygen and carbon,can be broken down by the plant. Nitrogen is an inorganic but plants can remediate it.

The terms rhizodegradation and phytodegradation describes the process in which plants roots or leaves are used to break down the organic substances in the soil An example of this is petroleum from leaky storage tanks, or roads.

PAHs, although organics, are structured chemically differently, and are can be more difficult to break down. They can be dealt with by using Phytoexcluders, which have a specific propensity not to take up the contaminant. This is more commonly referred to as stabilizing or capping an area, preventing erosion andisolating the contaminant from the air and translocation by the wind.

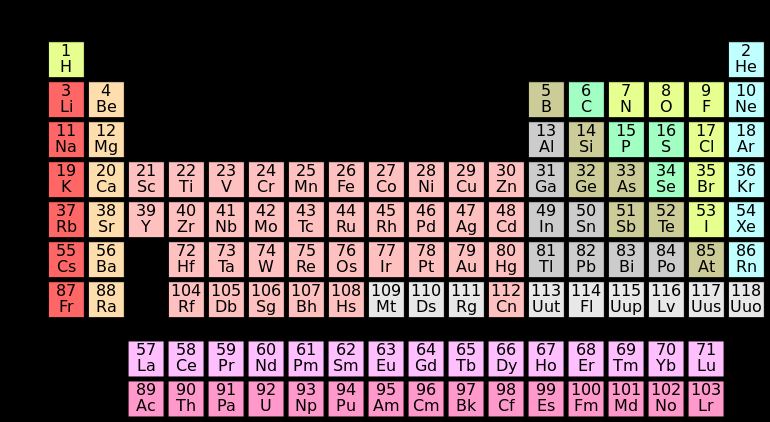

Inorganics are essentially elements found on the periodic table and cannot be broken down. Inorganic contaminants require extraction or stabilization on a site. If extracted with plants, the contaminated plants need to be harvested and disposed of safely to avoid depositing the contaminants back into the soil which they took it from.

The plants used to achieve all of these results, particularly in different zones, are still being studied.

Lead (82 Pb) is yet to find its plant match, and quite unlikely ever to since it is often tightly bound to soil particles, and difficult to translocate into roots, stems and leaves.

Modes of Action

There are six modes of action identified with plant material in developing phytotechnology:

Phytosequestration

Phytosequestration is the ability of plants to sequester certain contaminants in root zone. This is accomplished through several of the plant’s physiological mechanisms. Phytochemicals extruded in the root zone can immobilize or precipitation of the target contaminant. The transport proteins associated with the root also can irreversibly bind and stabilize target contaminants. Contaminants can also be taken up by the root and sequestered in the vacuoles in the root system.

Phytohydraulics

Phytohydraulics is the ability of plants to capture, transport and transpire water from the environment. This action in turn contains pollutants and controls the hydrology of the environment. This mechanism does not degrade the contaminant.

Rhizodgradation

Rhizodgradation is the enhancement of microbial degradation of contaminants in the rhizosphere. The presence of a contaminant in the soil will naturally provide an environment for bacteria and fungi which can use the containment as a source of energy. The root systems of plants, in most cases, will form a symbiotic relationship with the organisms in the soil. The oxygen and water transported by the roots allows for greater growth of beneficial soil microorganisms. This allows for greater breakdown of the contaminant and quicker remediation. This is the primary means through which organic contaminants can be remediated.

Phytoextraction

Phytoextraction is the ability to take contaminants into the plant. The plant material is then removed and safely stored or destroyed.

Phytovolatilization

Phytovolatilization is the ability to take up contaminants in the transpiration stream and then transpire volatile contaminants. The contaminant is remediation by removal through plants.

Phytodegradation

Phytodegradation is the ability of plants to take up and degrade the contaminants. Contaminants are degraded through internal enzymatic activity and photosynthetic oxidation/reduction.

(source: Wikipedia: Phytotechnology)

Click Here for a more technical explanation

A Cocktail of Contamination

Most contaminated sites have a “cocktail” of contaminants, and multiple strategies are most commonly used. There are also different conditions to consider, such as;

1.How deep is the contaminant?

2.Will the roots of a particular plant reach the contaminant or is it too deep; or

3. Is the contaminant protected by a layer of soil too dense for root penetration?

“PHYTO: A Resource for Site Remediation and Landscape Design” by Kate Kennen and Niall Kirkwood (coming Fall 2014)

Kate Kennen, my friend, an instructor at Harvard University Graduate School of Design and principal of Offshoots, is currently studying this topic and will publish her findings shortly. Offshoots, Inc is a hybrid design practice in Boston, MA offering landscape architecture, planning and productive landscape installation services.

She is co-authoring a book with Niall Kirkwood, director of Harvard University’s Center for Technology and the Environment. The book is titled “PHYTO: A Resource for Site Remediation and Landscape Design” and will be published in Fall 2014. The objective of the book is to translate this complicated science for designers and practitioners to utilize in every-day landscapes.